0.7.1 Release

Thread safetyA couple weeks after the 0.7 release I’m excited to announce the first patch release of 0.7.x series.

The theme of this release is a single, yet important, improvement: Thread safety.

In this post I’m going to dive deeper in the architecture of this change.

JDK 21 and Virtual Threads

As usual, after I announced a new release on reddit I got a few positive and inspiring comments and feedbacks, but out of all messages, one single sentence stuck in my head:

The only thing I think you should consider is some switch to turn off thread locals given JDK 21 and virtual threads.

While the suggestion hinted at a switch, some sort of runtime-based mechanism that could decide between thread locals and something else, I think Penna benefits more from being simple and straightforward.

Why is this a problem?

Let’s take a step back and think critically about ThreadLocal and how virtual threads affect Penna.

If we read the JEP 429, specially the section which mentions the Problems with thread-local variables, we can get a hint that,

at least for Penna’s use-case, ThreadLocal can be an issue both by it’s Unbounded lifetime and Expensive inheritance characteristics.

Imagine this scenario: an app running Penna is now using Virtual Threads to handle the requests. For Penna, before, that meant that each Virtual Thread

would trigger a cascade of allocations in Penna, as both Penna’s LoggingEventBuilder implementation and the code responsible for writing the JSON log message were attached to a ThreadLocal variable.

I can discuss the rationale for that in a separate post, but for now, it suffices to say that it was a pretty fair bet that it wouldn’t blow client application.

New technology, new challenges

Ok, so we’re dropping the ThreadLocal. How do we start?

We can do a “TDD-ish” approach here. Is it really a problem to run Penna on a virtual thread? JMH to the rescue…

| |

What do I want to prove with this test? Well, if it breaks, than of course I have to fix the code, but also it gives me a chance to measure how much memory, GC and throughput Penna has in a close to real-world scenario: a virtual thread will acquire some logger - possibly a new one? - and will write a few messages before shutting down.

First attempt, with the existing code and… It failed miserably (no surprise, Sherlock).

With a single thread only, it was filling the heap size for the test (8gb) quickly.

So the first measure was to reduce the buffer size from 32kb to 2kb. Now it doesn’t die out of memory gluttony, but instead we reach a few barriers:

- Logger acquisition can sometimes fail during the runs;

- For a test run with 16 threads, not only it performs poorly, but it also runs indefinitely, never finishing the test run.

So, in a virtual thread environment, we were paying the cost of doing a significant number of allocations. The runs were reporting about 4k ops/sec for one thread only 60 ops/sec for run with 16 virtual threads.

First shot

The two main components in this setup are the LoggingEventBuilder and the Sink. The first because it contains a reuse object - cheaper than allocating a new object at every log call - which is cleaned and re-populated with the new logging information. The second because it contains the buffer where the json is written to before dumping it into stdout.

So, it feels natural to group then together. In fact, we can have an object pool in which a tuple-like structure can hold a reuse LoggingEvent and a Sink:

| |

And an object pool for this object sounds like a trivial thing to build, right?

| |

So far, so good. Except, of course, we need to make this thread safe, otherwise two concurrent threads can update the allocations BitSet and they can get the same object at the same time. Also, we need to ensure we don’t go over our object pool size limit.

Synchronizing the method here wouldn’t help either as we need to lock on both acquiring and releasing the object from/to the pool.

Then, if we think about it, if we add a lock around the allocations BitSet, in the event many threads want to acquire a LogUnitContext object, we’ll make them wait for no reason.

Granular control

The final solution looks something like this:

| |

Considering the fact that both arrays are the same size, we can now have better control of our contention as tryLock will only return true once we’re able to get hold of an object in the pool, which in turn will only return to us an index that this thread is able to hold. Releasing an object now doesn’t hold or affect acquiring an object. The layer above will, of course, need to make sure this object is released after the logs is written - or even if it fails to write.

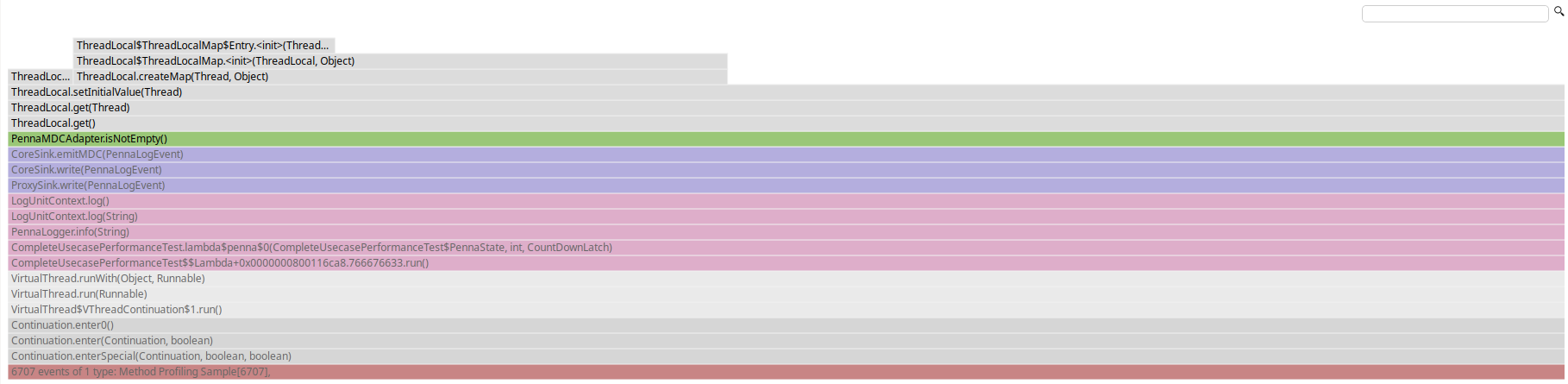

This shows up in the JMH test, as that test is now able to run for 1, 16 and 256 threads without issues:

Benchmark (threads) Mode Cnt Score Error Units

CompleteUsecasePerformanceTest.penna 1 thrpt 3 48389.452 ± 20980.696 ops/s

CompleteUsecasePerformanceTest.penna:dTLB-stores:u 1 thrpt 5990.455 #/op

CompleteUsecasePerformanceTest.penna:gc.alloc.rate 1 thrpt 3 61.279 ± 26.503 MB/sec

CompleteUsecasePerformanceTest.penna:gc.alloc.rate.norm 1 thrpt 3 1327.991 ± 0.647 B/op

CompleteUsecasePerformanceTest.penna:gc.count 1 thrpt 3 6.000 counts

CompleteUsecasePerformanceTest.penna:gc.time 1 thrpt 3 4.000 ms

CompleteUsecasePerformanceTest.penna 16 thrpt 3 7974.001 ± 1657.137 ops/s

CompleteUsecasePerformanceTest.penna:gc.alloc.rate 16 thrpt 3 152.502 ± 31.521 MB/sec

CompleteUsecasePerformanceTest.penna:gc.alloc.rate.norm 16 thrpt 3 20054.613 ± 41.570 B/op

CompleteUsecasePerformanceTest.penna:gc.count 16 thrpt 3 15.000 counts

CompleteUsecasePerformanceTest.penna:gc.time 16 thrpt 3 9.000 ms

CompleteUsecasePerformanceTest.penna 256 thrpt 3 692.376 ± 4654.997 ops/s

CompleteUsecasePerformanceTest.penna:gc.alloc.rate 256 thrpt 3 310.801 ± 2105.448 MB/sec

CompleteUsecasePerformanceTest.penna:gc.alloc.rate.norm 256 thrpt 3 470272.697 ± 32649.345 B/op

CompleteUsecasePerformanceTest.penna:gc.count 256 thrpt 3 31.000 counts

CompleteUsecasePerformanceTest.penna:gc.time 256 thrpt 3 22.000 ms

For a single thread it shows a 10x improvement over the ThreadLocal version and for 16 threads it is more than 133x faster.

The numbers, however, start to go down because of contention further down the chain, when the JVM tries to offload the buffers into stdout.

What’s next?

Penna 0.7.1 is now released with this change and I hope to get more feedback soon. There are a ton of things that can be improved, but this makes Penna 0.7.1 effectively ready for JDK 21.

One of the things I experimented with but didn’t commit to change yet is how the lock is acquired. By always starting at 0 we don’t benefit from the ring buffer that much. Starting off from a random position showed to be better for a single thread (or rather, while stdout wasn’t disputed by other threads), so it could be a way forward. Another alternative would be to use an atomic integer and store the values within runs, but this might add more overhead than necessary.

A bonus, hidden ThreadLocal issue “fixed”

Another ThreadLocal instance that was touched upon, but unfortunately still not removes was the MDC storage. That is by design, as MDC data is inherently thread-local.

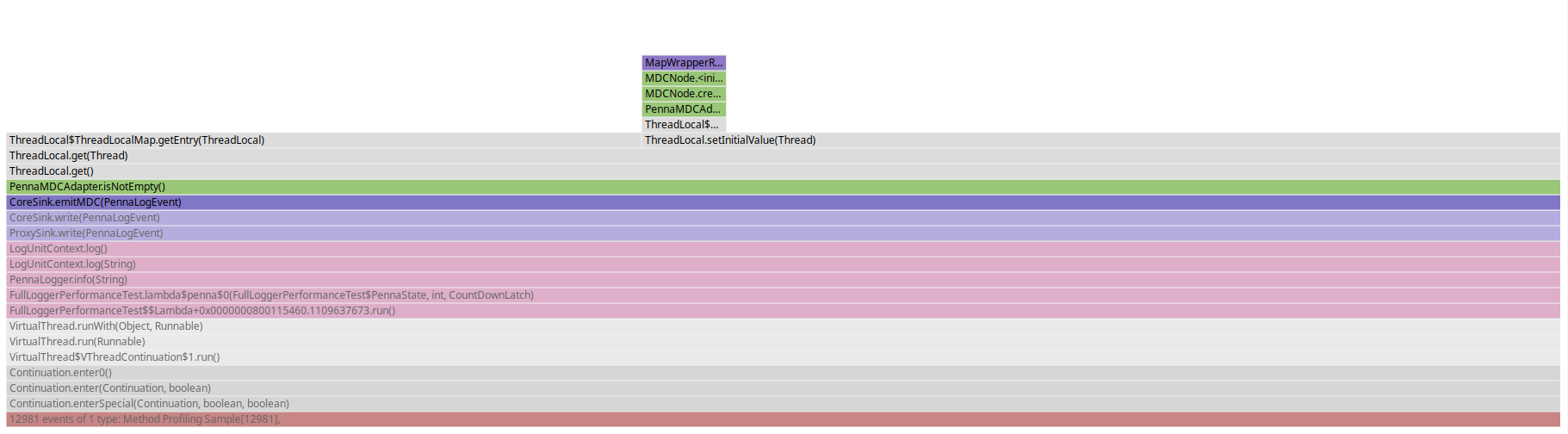

However, when looking at the flamegraph for those tests, a wild ThreadLocal popped out, even when MDC was not set:

So that was also re-engineered to avoid creating new objects. This nice little thig was made possible by using a sum type from a sealed interface:

| |

With this setup, the EmptyMdc instance in Mdc.Inner becomes a singleton object that, upon modification request (i.e. put as shown above), will update the ThreadLocal with a new instance of MdcStorage, contianing the new key-value pair. The storage, upon clear request, can also replace itself with the singleton proxy object.

This doesn’t solve needing the ThreadLocal yet, but makes it cheaper by not creating unnecessary objects inside the ThreadLocal.

A much better approach for JDK 21 would be to use ScopedValues, as proposed by JEP 429 and passing the values in the fluent API’s .addKeyValue() method:

Final words

This is a bit different than the previous posts as it went on deeper into the approach Penna adopted to replace ThreadLocal and be prepared for JDK 21. I’d really appreciate some feedback, questions or comments.

Penna is shaping up greatly at each release and your feedback is a huge part of its improvement. Don’t refrain from opening an issue, starting a discussion or sending me a message!

Stay tuned for more!