Performance insights: Guards, Time and Modern Java Features

Simple code can bear great performance benefitsA while ago I promised to go a little more in detail on the performance of Penna. There are quite a few interesting techniques in play for such high numbers to be achieved and nothing is too fancy or extreme that wouldn’t be useful outside, so it makes sense to go a bit in detail as it can be useful for other projects.

A word of caution

Take this and the follow up posts on performance with a grain of salt. The JVM is complex and, as such, there is no “silver bullet” when it comes to performance. As always, the mantra remains:

Measure, don’t guess.

Having that said, it is interesting how the recent Java features allow us to write performant and elegant code simultaneously and in this and the follow up posts I’ll try to go through some of the things used in Penna that were enabled by recent JVM/language improvements and can definitely be used outside of Penna with similar gains and benefits.

Set up

Let’s imagine a simple scenario: We have a logger that should log only messages of certain levels (say, info, warn and error) but nothing below it (debug or trace). At a certain point, during runtime, we should be able to either raise or lower the threshold.

A straightforward implementation would take the level and check it in runtime, whether we’re allowed to log or not, then only move forward and log if the message level is above or equal to the configured level.

The code would look like this:

This is natural code and there is nothing wrong with it, but looks are deceiving and there are some hidden details to this code that can make it not so performant.

Broader view

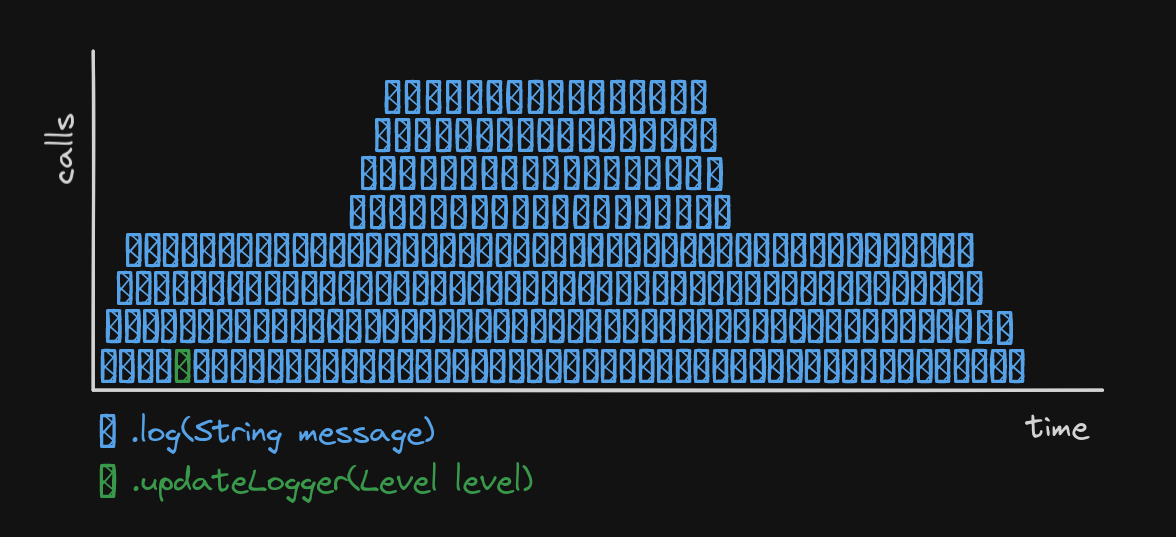

There are two hidden problems in that simple, seemingly harmless code: First, the log level, throughout an application runtime, changes much less often than a log message is written, but yet we pay the cost at all log call invocations. In fact, it can be that your application won’t ever change the log level at runtime. Truth be told, that will be true most of the time your application is running. And yet, we introduced a runtime evaluation that limits our code and taxes it with a hardly ever changing predicate evaluation.

The second is a bit more subtle, as it involves understanding how branch misses might affect the general performance.

As an application developer, you might be led to believe that most of the log calls are info, warn or error due to the code you end up writing, but in reality, there’s a substantial amount of debug and trace added by libraries under the hood. This essentially means that the CPU lacks a pattern to reliably predict branches,

so it can be thrown off-guard and has to discard work it had already done, because it failed predicting which code path the execution was going to take.

So, if we consider those two problems, we want to address them by paying the cost of level checking at once, as early as possible. Also, we want to reduce branch misprediction costs.

*-time

The first issue described above has a lot to do with time and, as this is a recurring theme in Penna’s architecture and design, I think it is relevant to take the time (heh) to talk about, well, time.

When I say time I don’t mean the continuum, infinite flow passing through the other dimensions of reality at a seemingly constant rate, but this is a good starting point.

If we imagine the time as an infinite line, your application will cross it orthogonally on various occasions. Keep up, I promise it will make sense.

When we design our application or library, when we draw a diagram about a certain layer, when we study an algorithm or data structure to implement some feature of the application, all those events in the timeline relate to our application. Also when we write the code, compile it, deploy it and when it runs. All those events are weaving marks in the fabric of time.

The grouping of those events in relation the state of the code is oftentimes referred to as some time. Most notably, those events that happen while the application is running, are said to happen during runtime.

There are other “times” of an application & library, such as the design phase time, the compile time, the packaging time & the deployment time.

In languages like C or rust we can move a lot of the decisions to the compile time using macros and preprocessors. In other languages, like clojure, macros are evaluated once, in early runtime.

Some decisions can be made before runtime, but the effects will only happen at the runtime. For example, a common case in java is when we pick the libraries that will be available in the classpath. Grouping, packaging & deploying the jars won’t cause any change, but once the application starts, the classpath is evaluated and libraries are loaded, the decision triggers the effect.

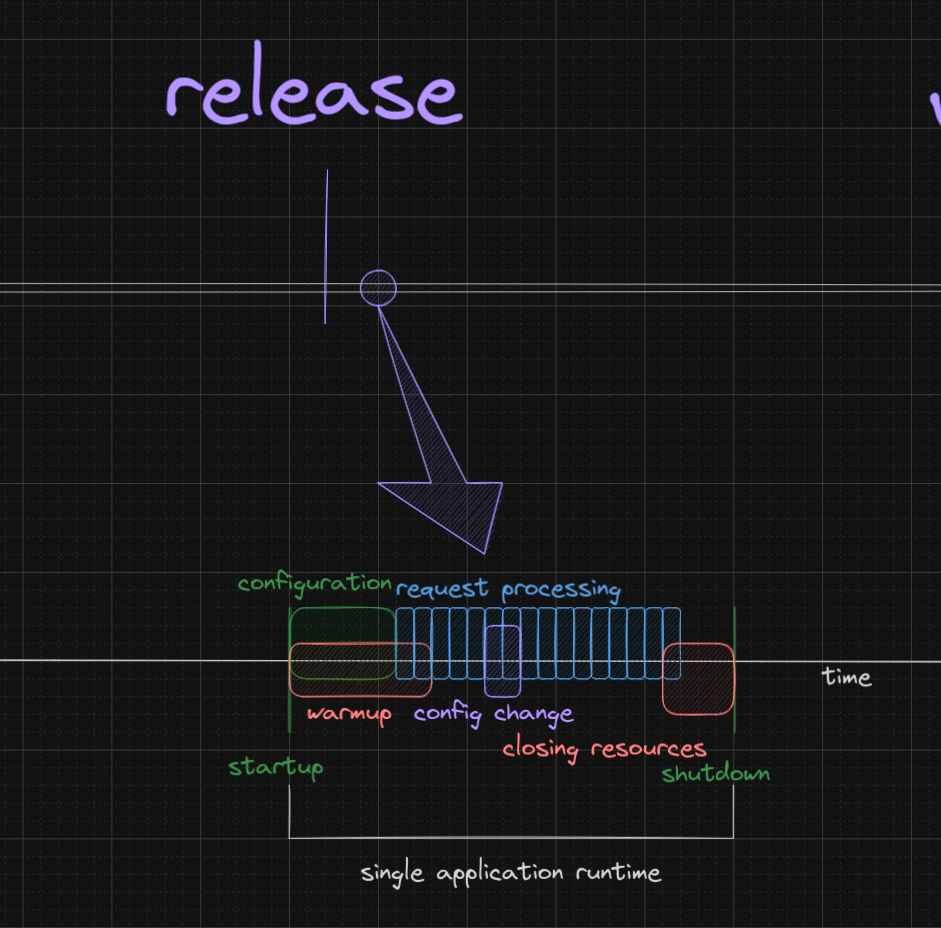

As many things happen in the runtime, I think it is fair to say that there are “sub-times” in the runtime, such as application initialization time, configuration time, thread start time, jvm warmup time, etc. Some of those might overlap and there can be some blurry lines in between. Also, different applications will have different sub-time configurations. Yet, the logic stays the same: In every application, there will be things that happen once the application starts and never after, things that happen constantly, things that, once happen, trigger other things to happen as well, etc.

Ok, why am I telling you all this?

I think it is important to be able to recognize those times and their relation to each other.

For Penna, it is clear that “configuration change”-time happens way less often during runtime than “log write”-time. Also, reasoning like this allows to decouple concepts that were seemingly coupled. For example, “log write”-time shouldn’t need to pay the costs associated with “configuration change”-time, because, in relation to one another, the log writing massively outweights the configuration change. Decoupling those concepts allow us to see this optimization opportunity more clearly.

Many other examples can be found: Writing logs incurring object creation cost, writing to stdout incurring the io channel opening cost, etc. Identifying those events, their occurrence rates, their relation between each other and how they affect the performance, by incurring costs, is a powerful tool to indentify performance optimization opportunities.

There’s an article about the fallacy of premature optimization that brings some very interesting perspective over the famous quote and I want to connect this time-related concept with how the article approaches the subject.

The full version of the quote is “We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil.” and I agree with this. Its usually not worth spending a lot of time micro-optimizing code before its obvious where the performance bottlenecks are. But, conversely, when designing software at a system level, performance issues should always be considered from the beginning.

When thinking in terms of the relative times that events happen in our applications, the (real) sentence from Knuth resonates well. Note my emphasis: where, in this context, referring to a time dimension, when in relation to other times. In our case, “configuration change”-time is impacting “log write”-time, and this is where the optimization should reside.

The modern java alternative

Back to code, the recent endeavor to make java modern and efficient brought features such as sealed types and default methods in interfaces, which we can use to approach an elegant solution.

In fact, Penna is using those and they are one of the reasons why it can achieve impressive performance results.

Let’s have a look at those log methods and think how we can re-write them without paying the “configuration change”-time costs.

Abstractly speaking, those methods act as gates for our log messages: If a log certain log level is allowed, it builds a log event object and passes it through the gate. If not, then it does nothing. We can logically break those responsibilities in two: building the log event and passing it through the gate according to the clearance level.

Building the event is inevitably a responsibility of this function, but we can delegate the logic of passing through the gate to something else, like a guard. This resonates well with our previous topic, as each of those responsibilities can happen at the adequate time, and some effects can be moved to minimize their impact.

In real life, when you arrive at a castle’s gate, there’s always a guard there. It would be inefficient if a guard would have to move to the gate only when there’s someone there, then once the visitor leaves, the guard retreats to the castle’s interior.

Penna follows this logic and the passing through of the log event is decided by a LevelGuard, which is a sealed interface with one concrete implementation for each log level:

| |

The astute reader will notice one thing: the default implementation is biased. That is intentional. In fact, if you look closely, you’ll notice that it is much the

same as the INFO level implementation should look like: INFO, WARN and ERROR are enabled, TRACE and DEBUG return the NOPLoggingEventBuilder instead.

This is to reduce the number of duplicated @Override methods with the same implementation and, as a consequence, the binary size of those classes.

It also allows for a simpler implementation of those classes as we know the DEBUG guard would only have to additionally allow the debug level as well as the

WARN guard should only turn off the methods for info, simplifying the implementation of those guards.

| |

Also, notice the clever NOPLoggingEventBuilder. It allows our code to look the same, but doesn’t cause the side-effect:

| |

With our LevelGuard knowing beforehand whether the requested level should forward to an implementation of LoggingEventBuilder that actually builds the event and logs it or if it should just throw in the do-nothing implementation, the concrete void trace(String msg) implementation will look the same regardless.

Now, before we move on, you might be asking me “but how specifically the sealed feature helps anything here”?

From the developer perspective, it gives us the reassurance that all the necessary Level enum values are mapped to a guard, no more, no less.

From the JVM perspective, we’re giving it more information for potential runtime optimization.

The performance optimization here lies on the use of guards, but using the aforementioned features allow us to write that code in a more legible and easier to reason way. I sure hope you reached this point and thought: “well, that wasn’t so difficult”, because the higher the cognitive load of a change is, the easier it is to mess up. Doing simple, elegant code can definitely lead to great performance, so the benefit of those features lie in alleviating the cognitive load.

An important observation: due to inlining and other JVM performance optimizations, changing the levelGuard instance can have some impact in the immediate application performance, but differently from the previous approach, that is amortized over time as that code path warms up and the JVM recompiles the logger class.

Talk is cheap, show me the benchmark

That all sounds wonderful in theory, but let’s look at some numbers, shall we?

The JMH benchmark below shows three possible scenarios: We only have enabled log levels, we only have forbidden log levels or we have a mix of those two. Note that after the Logger layer, the internal mechanisms are the same for writing the log event as json. For the benchmarks, both implementations will in fact write json

messages when allowed to, but instead of stdout, they’ll be consumed by JMH’s Blackhole, so the tests are not skewed by any IO fluctuation.

| |

And the results are:

| |

The numbers are interesting and there are many things we can learn from this.

For example, if we only look at the IfBasedLogger numbers, we’ll note that it has a consistent performance for whether we’re allowed to log all messages or we’re not allowed to log any of the messages, but it’s performance is drastically reduced (55% of the baseline) when both levels are in the same test.

Also, by using the LevelGuard approach, we’re consistent between only allowed and mixed levels, as there’s no branch miss.

A final interesting observation from the results is that doing nothing is so much more performant than doing a check. Using NOPLoggingEventBuilder throws the check-based version off the park aggressively with its three orders of magnitude faster results.

Conclusion

Remember, the numbers above are results from a synthetic benchmark, so it is not like the real world numbers will look the same. Yet, we can draw a few important conclusions from our experiment.

Evaluate early and avoid paying costs continuously for rarely changing values is definitely something that is intrinsic to Penna’s performance and can be applied in your applications as well. Again, identifying the rates at which events happen in your application will give you another dimension to think where to optimize.

Performant code doesn’t have to look ugly. A common misconception is that performant code has to be cryptic and hard to read. I argue that it is most often than not the contrary.

Performance comes from design, as intentional code structure definitely impacts the performance output of the application.

Modern java is your friend and allows for nice features such as sealed types and default method implementation allow for concise, clean and performant solutions. In fact, branchless code doesn’t need to be using clever bitwise operations to dodge if blocks. It can be lifted to the code architecture and dealt with using intentional and thought through design.

While not discussed in this article, the fact that we opted to use a sealed interface instead of the usual interface had a (small) positive effect in the performance, for sure, but going into those pesky details would make this article far more extensive.

Finally, Measure, don’t guess is your mantra whenever talking performance.

And with that we’re done with the first post on the performance series. As always, feedback is appreciated and welcome! Don’t hesitate to reach out to me with your thoughts, ideas, suggestions and experiences. The github discussions section is a great place to leave some feedback.