Performance insights: Engineering for high performance

The performance of our projects is a byproduct of the process we adopt developing itThis is the second article in our series of Penna’s performance insights. If you haven’t checked the first one yet, make sure to have a look!

I’ll take advantage of the recent release of the 0.8.x series to kick off this article and talk a little more as to how Penna manages to achieve really good numbers when compared to other slf4j backends.

High performance software engineering

The JVM is an efficient platform and capable of incredible performance, but that doesn’t mean that all code in Java will immediately be blazingly fast. In fact, although some languages are intrinsically capable of being faster than others, your code won’t automatically be faster just because you’re using a faster runtime. To achieve good performance, even if you have a solid foundation that allows for great throughput, you must plug the pieces of your software in certain ways, so I don’t think it makes sense for us to think of micro-performance tricks before we talk about using software engineering for this goal first.

And some languages like Java can offer so many features that there can be multiple different ways of achieving the same solution, with varying performance, scalability and readability traits. It is wise to understand those differences in order to make the right trade-offs. However, things might not be as clear cut as we imagine. During the development of Penna, some changes I was betting would optimize throughput caused little to no effect. Other changes would allow for a much better result than I anticipated. So this is the practical advice before we get our hands dirty with the details: Whenever you are talking about performance optimizations, don’t trust blindly that your change will have the intended results. Measure. Verify. Then check your tests and verify again. So although we understand, in general, which direction certain approaches can take us, the reality can be much different as oftentimes there are more factors involved than we generally think of.

So we want to write a new, lean and efficient program. The first thing we need to do is. Think. Well, not in the obvious sense. We frequently tunnel vision on what we are trying to build, specially when we’re dealing with small projects, and end up forgetting about other satellite aspects. So here is where the thinking part goes: We try to think outwards from this core idea. What is it that you are trying to build? Where do we expect to run it? How should the customers interact with it? What is the worst acceptable performance that it can have and still be viable? Those are popularly called non functional requirements and they’re a fundamental aspect of our project. A system that takes one hour to process will definitely be a rejected by most people, unless it’s a credit-card consolidation intra-night batch job.

I would say then that work of writing performant software is significantly easier if you start thinking about your application’s performance requirements before implementing it. Event if you don’t end up writing it to meet those requirements immediately.

As we write software, we’re always faced with multiple ways of addressing the problems, as said above, so we need to chose one approach over the other. If we know, beforehand, the answers to those questions, we can be more assertive that our decisions will lead to our desired goals.

It is intentional, instead of accidental, software design. And we achieve that through using this kind of metadata from our own project to guide our decisions. This reflection over our requirements will give us dimensions that we could use as reference. And it is a good parameter for when we analyze our intended solution through different lenses.

Another perspective that we can get from (or even better if we can set on) our project is about the problem space it is trying to address. I’m a big fan of the philosophy of “doing one thing and doing it right” which, unfortunately, was summarized so well that over time we lost the ability to understand the knowledge that is engrained in its core. Hear me out, the fact that Penna sets to solve a single use case has both direct and indirect benefits to its throughput and memory consumption, to its maintainability, asset size and likely to other unthought of areas. So its specialized software nature opens up the possibilities for performance characteristics that won’t be as easily achievable on software that aims to cover a larger surface.

Avoiding unnecessary abstractions

As we transition from the high-level overview of our system to the implementation, we should aim to apply those concepts and use them as reference for the concrete solution we ought to deliver.

I fear one of the worst hereditary traditions of the rite of Java is to write abstractions. The need for strict layers, annotation-based injection, indirection and complex logic for the sake of encapsulation. Do not encapsulate what you don’t need, Do not abstract what you don’t need. Don’t write unnecessary intermediary layers for “what if” scenarios. It has immediate performance implications in your application, as your code won’t be as easily optimized by the underlying layers, as well as indirect implications, as your code will be harder to reason about, will require increased cognitive load to maintain and simple optimization patterns will be far less obvious to spot.

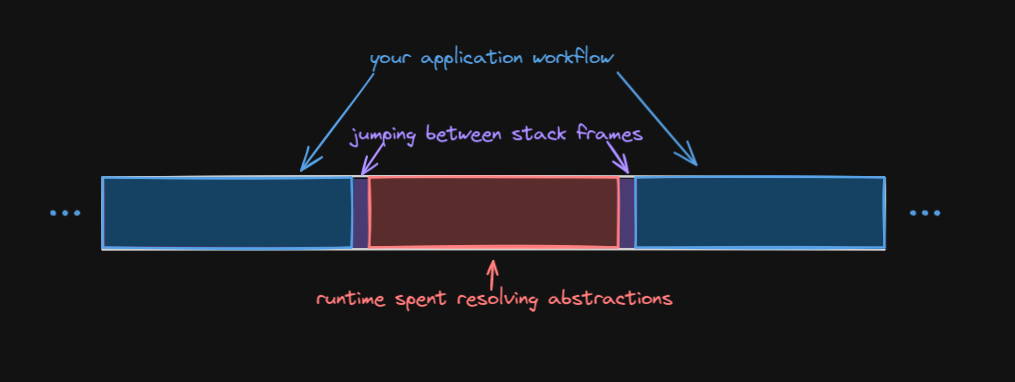

When you write abstractions, you are effectively adding functions in-between the “intended” application workflow. Those functions cost. They are frames in the stack, there is some state to be saved, some bookkeeping of where in the program you runtime is has to happen. And even worse, you can be spending runtime processing time to resolve abstractions. It’s no surprise that modern languages are investing in things like zero-cost abstractions, aka compile-time resolution to some necessary decision making. If you haven’t yet, have a look at the previous article, because this concept of the right time to perform actions has been touched upon there a bit more in detail.

So, what is a “simple” way of making you app run faster? Make it less abstracted. Now, there’s no reason to remove all the glue code as well. Some abstraction might be necessary to keep your code cohesive. There’s not single answer to this question because each project will have different requirements, different purposes and different expectations. Try to think from the perspective of your project. Use the guidelines you from our previous chapter to direct you.

Intentionally make room for performance

Now, another thing that often comes to mind when talking about performance is the right time to jump into performance optimizations. This section is inspired by Casey Muratori’s answer in this tweet:

Both are bad. The correct approach is to keep in mind what will need to happen for high performance, and ensure throughout the process that your design will always permit full optimization.

— Casey Muratori (@cmuratori) March 18, 2024

So, don't think performance "first" or "last". Think "performance-aware throughout". https://t.co/7Z5bhgf45E

I think this resonates well with the approach we’ve been taking so far.

You see, the mere fact that you’re spending some time considering the scenarios and not jotting down ideas will allow you to intuitively (or even better if supported by theory or experience) make conscious decisions about your system in a way that it will likely perform better, allow an algorithm to be replaced by a more efficient one or at least ensure it can be more easily refactored and replace that section when better performance is needed. On top of that, we have our requirements to guide us, so we won’t be exploring uncharted territory throughout the project’s lifetime.

After the design phase, even if you picked the wrong algorithm, or a sub-optimal data structure, you’ll have room for improving. We’re harvesting the fruits of the harder work we had put up before. And that is because you only truly know the performance of a system when you measure it, when you see it running with your own observability and monitoring. The same system can behave completely differently depending on the platform it’s running on, the amount of users it’s serving or whether it is scaled horizontally or vertically.

There will surely be some cost associated with refactoring, we can’t get away from it. And it is fine, because the idea of planning your system from the perspective of its requirements is not to remove this cost, but to reduce it. Trying to come up with the perfect algorithm from the start can demand high loads of cognitive effort, delay the project or make it more complicated that necessary. The pragmatic approach is to shorten the release cycle, measure and improve. Thus, the design work should be limited to provide you with directions, not concrete solutions.

Anticipating the performance problems can be super tricky, not only because we’re reasoning on a hypothetical scenario of highly abstract concepts, but also because a system is composed of so many different components that the way we do the plumbing between them is just as important as the structure of those very same parts. And I mean plumbing intentionally because throughput through a system is very much like fluid dynamics. So, in this futurology exercise we’d not only have to try to foresee how the components will respond but also predict the optimal arrangement that minimizes bottlenecks. And it is often the case that our bottlenecks are in places we haven’t even considered in the first place.

So my advice here is: Skip the guesswork. Stick to thinking in terms of principles and guidelines for your project. The design phase should allow you to approach performance from a macro level. Measure and optimize through iterations, and it should be much simpler to approach performance this way given your design accommodates the necessary changes.

Boundaries for a safe high performance runtime

This next subject hurts my functional programmer’s heart, just a little. It’s easy to grow fond of clojure and scala’s immutable types, but here we should be pragmatic and a little stoic, and accept reality as it is: mutating values is much more efficient.

There are a couple of reasons for that, such as not having to allocate memory, not copying values over and not polluting the pool with garbage data that will require a GC pause. This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t use immutable types. We should better know when to use them. For example, one of the benefits often brought up by seasoned functional programmers is that immutable types are a great tool for defensive programming. And this is true.

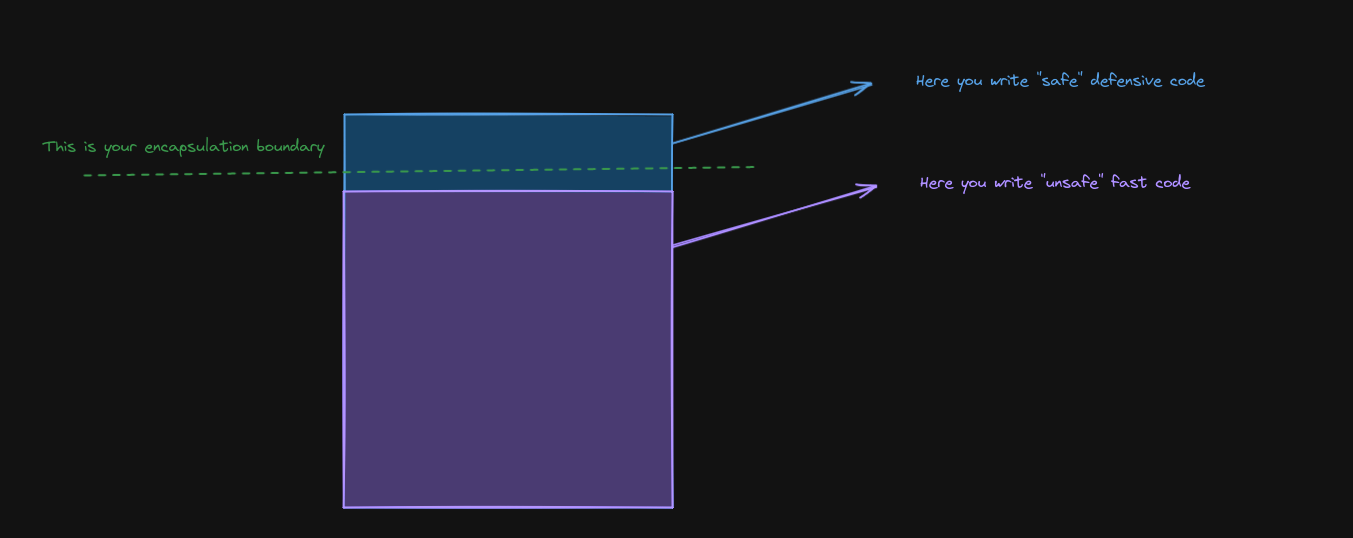

Yet, we don’t necessarily need to be defensive inside a method that interacts with another method within the same class, as the code locality is usually enough of a guarantee that we won’t shoot ourselves on the foot. This central piece of our logic is “safe” for “risky” mutability and we can expand the borders of our “safe” zone based on our confidence that it’ll remain safe at that expanded context.

To illustrate this idea, let’s think of cars. Although they are capable of achieving much higher speed that what we usually drive them at, the environment determines how safe is it to speed up. A bumpy road, a lot of traffic or narrow streets will force you to slow down. In a racetrack or a German autobahn however, you have conditions to drive safely at a much higher speed, because the environment allows for that. It’s the same concept, we need to ensure our boundaries allow for this kinds of optimizations.

As we grow those boundaries, we need to account for things like parallelism & synchronization and object longevity. For example, objects usually “live” the at most the same duration as the actions they’re intended to be used on.

So an HTTP request object for example, would live until the response is sent and then it is deemed free and can be released by the GC. But if we stretch its lifespan past those boundaries, we need to be sure that the second time this HTTP request is used will look exactly the same as if it was just instantiated, so nothing is left behind. Keeping track of those long-lived objects is a known pattern called Object Pooling. Should we pool our objects? Well, this is the kind of answer you’ll have to think for yourself. Remember to use your design as a guide for performance here.

So, in the core of our code we have complete trust that it won’t corrupt the data and we can let our guard down, but where does it stop being safe to play with fire? We should strive to be defensive on the borders of our code, where the scope of the data extends beyond our control. This way we can encapsulate the fast-yet-risky section of our code, safeguarding the access to this “unsafe” code.

I find it very useful to use the Java Modules for that. Some parts of your application are private. No one sees them outside your application’s scope. Then, you have a few select namespaces that you opt to expose to the outer world and those are the places where you’d want to impose defensive programming techniques (like the immutable data structures, for example). It’s a namespace-level encapsulation to allow for some sanity before entering your trusted zone. An Anti-Corruption Layer if you wish.

Another very interesting idea that resonates well with this concept is to model the types in a way that invalid states are unrepresentable. There are plenty of articles and videos on the subject, so I’ll keep it brief here (but hopefully this sparkles your curiosity on the topic). In this context, we want not only to keep our boundaries safe and sound but also avoid that the data that comes in will invariably work. If negative numbers could break your function, we validate the input. If there are only a handful of valid strings for our logic, we move those options to enums. If a parameter is only used in conjunction with one of the options, then instead of enums we could lift the choice to a sealed type, each with their set of required parameters.

The point is, we can make use of the type system to increase the safety of the inner layer by making the contract stricter. This way we’re not only closing down unsafe access, but we’re also dramatically reducing the chance of crashing. We’re building the best environment for running faster.

Conclusion

Differently from the previous article, this has been more of a theoretical writing. Yet, I think there is a significant benefit of trying to approach perfromance from an application design point of view and I am a strong believer in “intentional” software architecture.

Still, although approaching performance from distance, there are a few concrete suggestions that you can apply to your ongoing or next projects, without necessarily treating performance as a high-complexity kind of problem.

Depending on the outcome of this one, I might write a third article on this Performance Insights series, so let me know your thoughts. Also, don’t forget to try out Penna! As I mentioned on the introduction, I have recently released the 0.8 version with many great improvements to the overall ergonomics of the library. As always, feedback is appreciated and welcome! Don’t hesitate to reach out to me with your thoughts, ideas, suggestions and experiences. The github discussions section is a great place to leave some feedback.